Tellima Grandiflora

This native British Columbia plant, also referred to as fringecups, is the only species in the genus Tellima.

This website was created for Mr. Ehl's BC Plant Project in Life Sciences 11 by Cyrus Yip and is open-source.

Taxonomic Classification

Evolution

The flowering perennial plant has evolved several adaptations that aid in its great success in western North America, sometimes considered slightly invasive. Fringecups have developed shade tolerance, allowing them to grow in shaded areas of forests. Going back further, Angiosperms developed flowers for attracting pollinators, allowing for much more efficient reproduction compared to wind-based pollination. The fringed flowers of the fringecups are used to attract pollinators.

Environmental risks

Tellima grandiflora is considered secure by NatureServe, the most secure conservation status. The status is lower in some other areas, but it is also considered secure in British Columbia. While there are currently no risks to the plant, it shares many other plant's environmental risks, such as climate change and habitat loss. If sea levels rise enough, the plant's water could be mixed with saltwater, which would be very damaging.

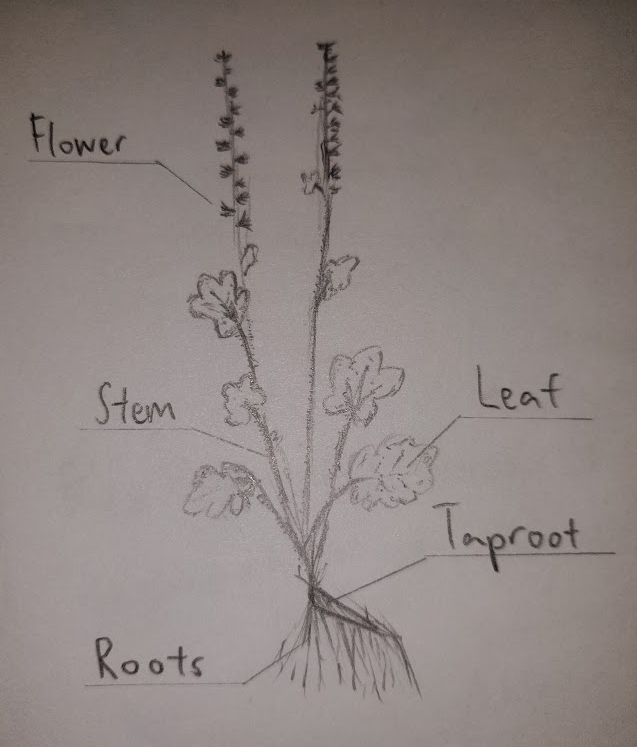

Diagram

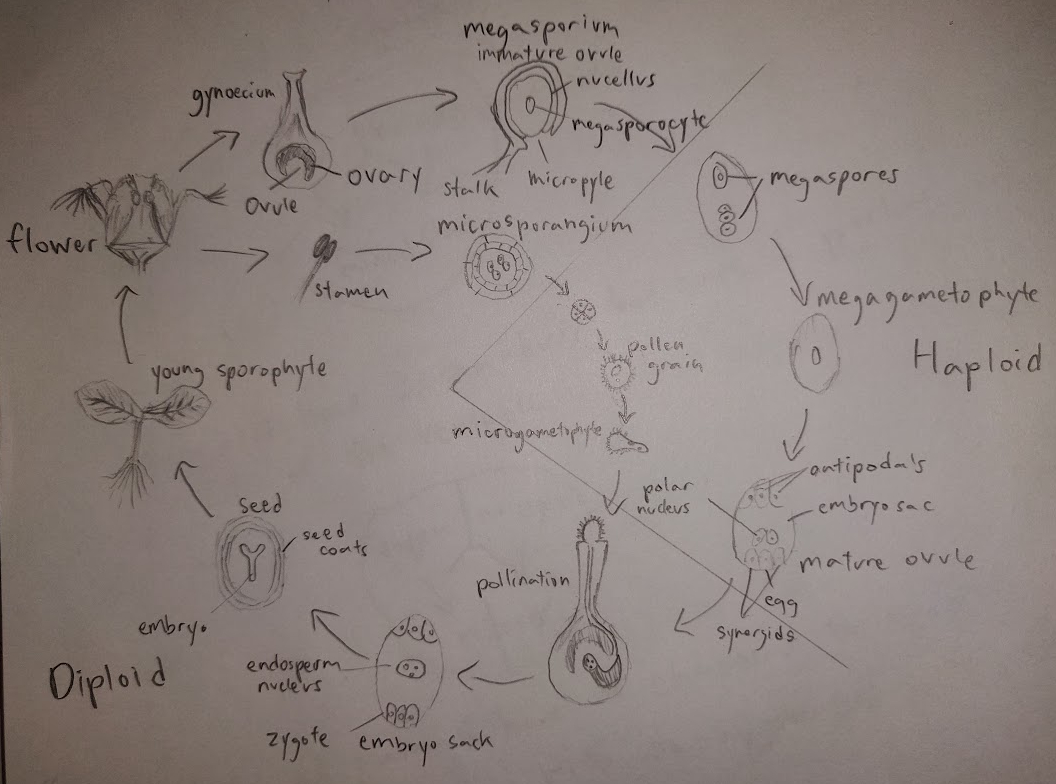

Reproductive Cycle

First Nations Uses

Tellima grandiflora was known as a special medicine for the Ditidaht First Nation that lived on Southern Vancouver Island. In Washington, the Skagit people crushed the plant and drank it as tea for sicknesses such as lack of appetite.

Modern Uses

Nowadays, Tellima grandiflora is pretty useless. It is primarily used as an ornamental plant in gardens and as ground cover due to its attractive fringed flowers and fragrant aroma.

Habitat

Tellima grandiflora is native to western North America's moist and dry forests. They thrive under partial sun and light shade with water, such as in moist forests, thickets, and along streams.

Works Cited

- Britannica, and The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Dicotyledon.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Jan. 2023, www.britannica.com/plant/dicotyledon. Accessed 25 July 2023.

- Cronquist, Arthur, Paul E. Berry, Martin Huldrych Zimmermann, David L. Dilcher, Peter Stevens, and Dennis William Stevenson. “Angiosperm.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 3 June 2023, www.britannica.com/plant/angiosperm. Accessed 26 July 2023.

- “Fringe Cups - Tellima Grandiflora - PNW Plants.” PNW Plants, pnwplants.wsu.edu/PlantDisplay.aspx?PlantID=310. Accessed 26 July 2023.

- George Wayne Douglas, Dellis Vern Meidinger, Jim Pojar, G.B. Straley. Illustrated Flora of British Columbia. 2023. Vol. 6, B.C. Min. Environ., Lands and Parks, and B.C. Min. For., 1998, pp. 110–111, www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/pubs/docs/mr/Mr104.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2023.

- Giblin, David, and Kevin Armitano. “Burke Herbarium Image Collection.” Burke Museum, Burke Museum Herbarium, burkeherbarium.org/imagecollection/taxon.php?Taxon=Tellima%20grandiflora. Accessed 26 July 2023.

- Mackinnon, A, Jim Pojar, Paul B. Alaback. Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska. Vancouver, Lone Pine Publishing, 30 Nov. 2004, p. 167.

- “Missouri Botanical Garden.” Tropicos.org, tropicos.org/name/29100773. Accessed 25 July 2023.

- “Plants and Climate Change.” U.S. National Park Service, 22 Dec. 2021, www.nps.gov/articles/000/plants-climateimpact.htm.

- “Tellima Grandiflora.” NatureServe Explorer, NatureServe, explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.152849/Tellima_grandiflora. Accessed 26 July 2023.

- “Tellima Grandiflora (Fringe Cups).” Gardenia.net, www.gardenia.net/plant/tellima-grandiflora. Accessed 27 July 2023.